At approximately 02H15 this morning, 26 April, a huge shudder was felt throughout a large area of Govan Mbeki Municipality.

Social media started bussing with the news especially on “Secunda en sy mense praat saam”.

Residents related to how the shudder woke them. Some even said that there were two shudders.

This morning The Bulletin contacted Sasol Mining to enquire about the possibility of mining activities. Sasol Mining checked with the Pan African resources (Gold mines) and confirmed that the shudders were not due to any mining activities in the area.

The shudders were felt in Kinross, Evander, Secunda and Trichardt.

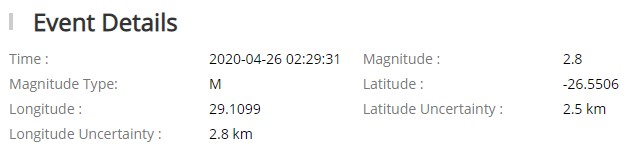

Speculation continued but several people visited the geoscience website that confirmed a seismic event near Middelbult mine.

This could be indicative of an earthquake, but the website warns against speculation until finally confirmed.

What is significant is the measurement of a magnitude of 2.8. Friday’s cracks in eMbalenhle appeared to be underground mining activities (not confirmed yet). But if so, it did not even register as a seismic event.

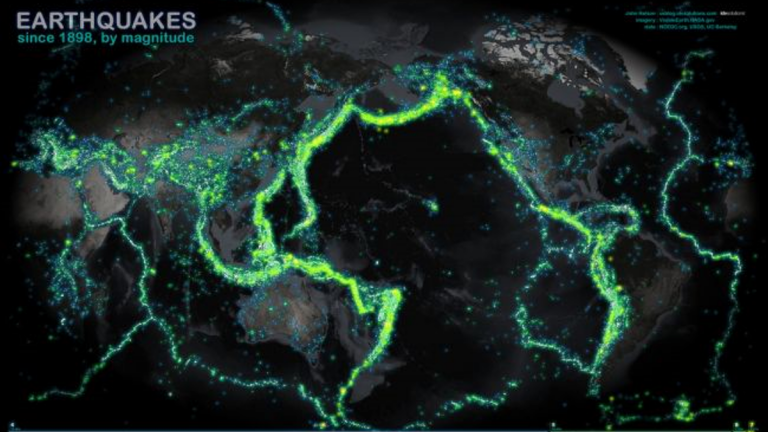

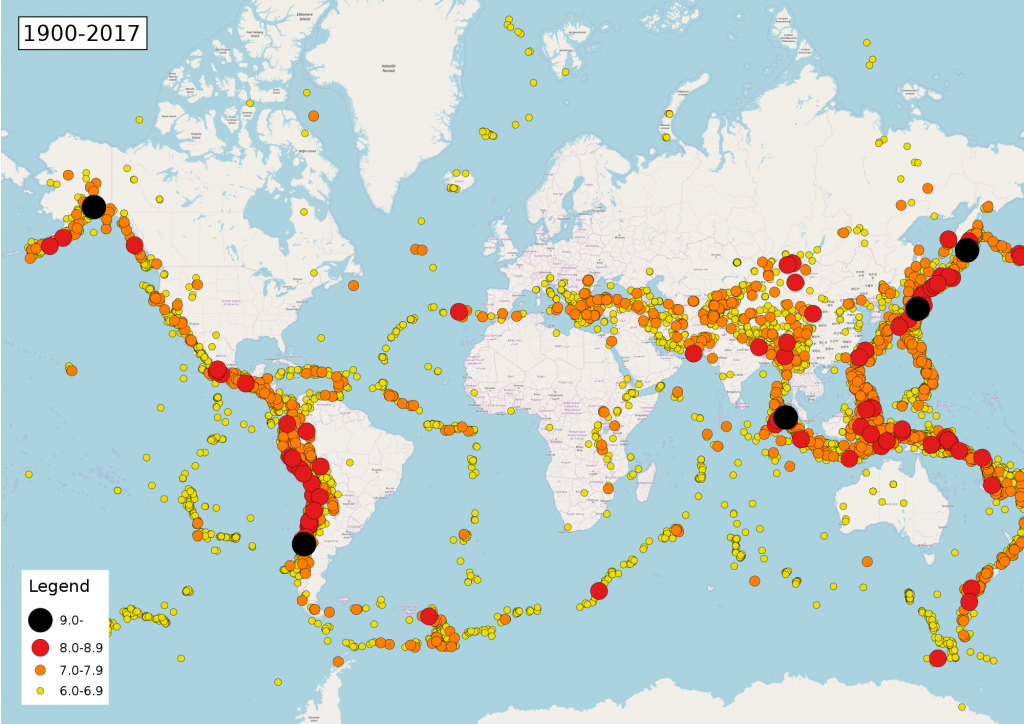

South Africa is lucky not to be on top of faults in the earth’s crust and therefore do not experience a lot of earthquakes.

This event, however, should be treated as an earthquake at this stage.

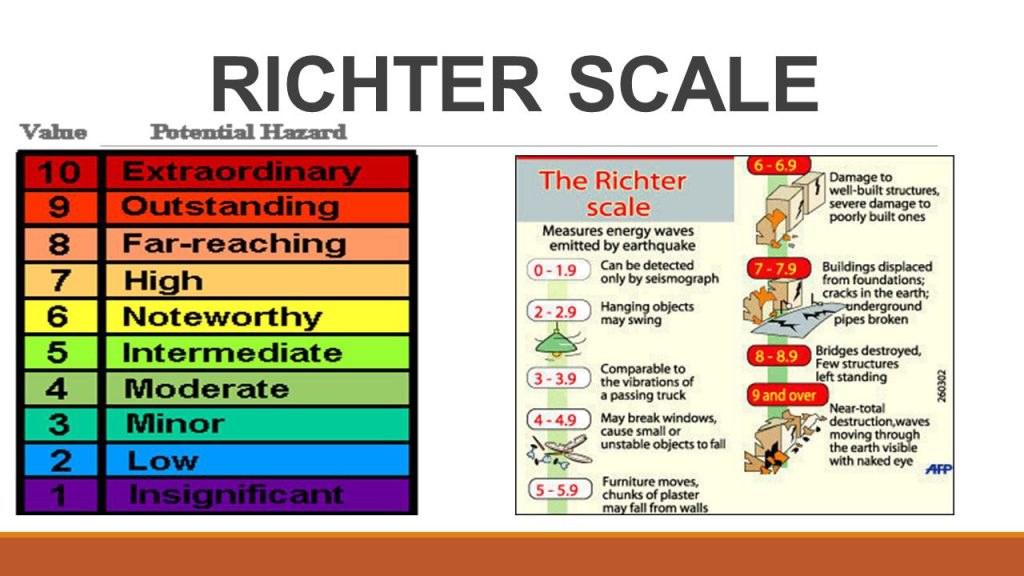

The familiar Richter scale (which is not a physical device but rather a mathematical formula) is no longer widely used by scientists or the media to report an earthquake’s size.

Today, an earthquake’s size is typically reported simply by its magnitude, which is a measure of the size of the earthquake’s source, where the ground began shaking.

While there are many modern scales used to calculate the magnitude, the most common is the moment magnitude, which allows for more precise measurements of large earthquakes than the Richter scale.

In the news, however, when an earthquake’s magnitude is given, the scale used to calculate the magnitude is not usually specified since the modern scales are all very similar.

A network of geological monitoring stations, each with instruments that measure how much the ground shakes over time called seismographs allow scientists to calculate an earthquake’s time, location and magnitude.

Seismographs record a zigzag trace that shows how the ground shakes beneath the instrument. Sensitive seismographs, which greatly magnify these ground motions, can detect strong earthquakes from sources anywhere in the world.

From these measurements, a quake’s magnitude is usually reported as, for example, a magnitude-7.0 in the case of the earthquake that struck Haiti on Jan. 12.

Based on their magnitude, quakes are assigned to a class, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. An increase in one number, say from 5.5 to 6.5, means that a quake’s magnitude is 10 times as great. The classes are as follows:

After an earthquake strikes, its magnitude is continuously revised as time passes and more stations report their seismic readings. Several days can pass before a final number is agreed upon.

Information in this article contained writings, images and videos from:

Brett Israel is a staff writer for OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to Life’s Little Mysteries.

Portions of this work include intellectual property of the COUNCIL FOR GEOSCIENCE and are used herein by permission. Copyright and all rights reserved by the said COUNCIL.

Wikipedia

www.livescience.com/